Formative Assessment Design 3.0: Technology Leveraged Image Analysis and the DBQ

Posted on Aug 16, 2019 Leave a Comment

Context and Purpose

As I’ve written before, Document Based Question (DBQ) is critical for the Social Science student and provides the ultimate application of historical thinking and reasoning. It requires that students read various sources and understand them such that they can cobble together enough information from multiple sources to respond to a question. Ultimately, transference to the contemporary world is the goal, either as a powerful tool for interpreting contemporary events or applying this skill to the workplace.

The DBQ is not often used in the average Social Science and History classroom. Advanced Placement (AP) classes use them as part of the learning and assessment process to prepare students for the AP Exam. Nevertheless, the average student and curriculum ought to use more DBQs—however challenging they may be. The typical DBQ asks a higher order thinking question that can only be answered by evaluating various sources, typically maps, images, or written statements from a particular historical period. Students write a response to the prompt by using the documents as evidence for an argument or historical claim. Students then write a response to the prompt.

Depending on the designed outcome, the DBQ is the ideal assessment. Typically teachers want their students to learn how to synthesize multiple pieces of information into a coherent argument, usually around other reasoning skills like Cause/Effect, Continuity/Change, and Compare/Contrast. A typical question in this order might be “Using the following documents, evaluate the extent to which European perception of Native Americans changed or stayed the same from 1500-1850” These types of questions assess a variety of skills and competencies, but they are time-consuming to create and grade.

The DBQ requires analytical, reading, and writing skills, among others. It is unrealistic to assume students have each one of these skills already. Like math, one missing skill can lead to a critical mistake that calls into question the entire problem. To that end, we need to make sure that each skill is given proper attention.

Perhaps one of the most fundamental skills that needs to be taught is the ability to read images. Different from reading a text of words, students need to practice reading the text of political cartoons, photos, graphs, charts, and maps. From these sources, students should ultimately be able to identify the image subject, specific content, argument, and finally, the bias or point of view (POV) of the author. Formative assessments on these “essential skills” will be vital for student success.

To that end, this assessment will help develop and evaluate students ability to read images for meaning, utility, and bias.

Assessment Instructions for Learners

Students will be provided with the following instructions and take part in the learning assessment:

Class Activities and Learning Agenda

- Students will first share their prior-knowledge of Native Americans and their relationship with Europeans by sharing with their peers in a group Flipgrid (an asynchronous social-media inspired video creation tool that can be either private between teacher and student, or leveraged for student interaction and discussion. This tool is best for this purpose because it allows for easy conversation beyond the four walls of the class. Students can take the feedback from the teacher and rewatch according to their needs. Moreover the conversation is continuous and already integrated into the students’ iPad and Canvas in my classroom).

- Students are free to talk about anything they know. (This is to assess student prior knowledge and identify a baseline for where each student is at the beginning of the assignment)

- Students will then take part in a class discussion of a few projected etching of Native Americans by contemporary European artists from 1500-1850. These images are part of a Google Slides presentation entitled NOBLE PEOPLE OR BEASTS? AMERINDIANS THROUGH THE EUROPEAN EYE — A Critical Thinking Analysis. For each image displayed, students will make observations on the nuances, details, and reflections on the pictures shown. This will be done using Pear Deck, through which the teacher will ask students key questions. Through Pear Deck, students are given a version of the Google slide deck with interactive questions and tools to point to places on the slide. Using these tools, the teacher can ask students to identify certain elements of an image. On the teacher’s screen, all the students responses will be displayed privately or anonymous projected over the image for quick identification of learning or opportunities to reteach. The teacher will prompt students to reflect on the values and ideas of Christian Europeans. They will consider what religious ideas and structures these people held. What figures (like the motif of Adam or God creator) were essential to their belief systems?

• With a partner designated by the teacher, each pair of students will choose one of the following images to analyze in the same manner as done above with the whole class. Students will consider the author of the image, the audience of those consuming the image, and the specific details associated with the image (figures, actions, tone, religious imagery, etc.).

• Following this pair-think-share, students will then work on a collaborative board for each image using a Padlet in which each group (and others who want to help), can write key words, observations, and ideas under each picture. This tool is helpful for collaborative sharing of words and ideas that can be digitally shared or projected.

• After a quick discussion of the students work on the images, the teacher will read a brief primary source passage on how Europeans viewed Native Americans from 1844, an excerpt taken from a children’s history textbook.

• (SIDE QUEST) For those student teams who have not used Flipgrid or Clips before, they will get a little extra boost! I will work with each team individually to get them up to Flipgrid-speed (and discuss their images with them a little…shhh, don’t tell).

Assignment Instructions (for students)

In collaboration with their partners, students will create a short video using Clips on their iPad. This Apple creative app allows students to take or curate short video clips and easily edit text or sound for a creative video presentation. Clips is easy to use and can create a short quality video with little software learning-curve. Students will then post this Clips video to Flipgrid to share with their peers. Students will respond to the following prompt using evidence from the sources discussed in class:

Evaluate the extent to which European perception of Native Americans changed or stayed the same from 1500-1850

These are the Assignment Submission instructions that should be given to the students:

• Make sure that your video is under 5 minutes (time limit on Flipgrid)

• Make sure that you pushed your creativity.

• Make sure that you pushed your critical thinking.

• Make sure that you used all the documents (images, texts, etc.)

• Make sure that if you have questions, you ask!

• Make sure that you have fun!

Feedback and Instruction

Upon submission of the Flipgrid, the videos will be placed in a holding spot awaiting teacher evaluation and feedback. I will give verbal video feedback for each video, highlighting specific aspects of the content and process of learning and use of technology for creativity.

Students will be free to change any content or technical/creativity aspects of the project in clips after I give the feedback. I can also give further feedback if so needed and/or desired.

Once the video is complete to the students liking and teacher satisfaction, their Clips/Flipgrid video will be posted to our class page where students can will watch and share what they learned from each other’s amazing work.

As a formative assessment, the point is that students are growing and learning through the process. The following skills (as well as some content knowledge) will be used and assessed: analyzing images, using more than one piece of evidence, and using evidence to respond to a question. These same skills will eventually be used and applied with other types of media, graphs, and charts in future assignments.

A Reflection on Assessment: My Journey through CEP813

Posted on Aug 16, 2019 Leave a Comment

At the heart of assessment is identifying what students know and don’t know and shaping classroom experiences to deepen student learning. I began CEP813 “Electronic Assessment for Teaching and Learning” with this fundamental view. Over the last several months, my understanding of assessments has deepened in exciting and frustrating ways.

I began seeing assessments as thermometers, mirrors, and pageants.

Assessments as thermometers are ways to gauge student understanding and mastery during the process of learning. Much as a Thanksgiving turkey is checked for temperature, smells, sounds, and over-all look, so too is proper formative and summative assessment. The analogy is not perfect. In reality, formative assessment (assessments for learning) are lessons, activities, and tasks through which learning occurs and by which the teacher can measure learning. The latter element is more summative (assessment of learning). In a certain way, all lessons, activities, projects, and tasks have a particular formative and summative element to them. This more sophisticated understanding has come from reading on social constructivism and behaviorism in the first module in CEP813. Seeing learning as an active process through which students construct knowledge together is a challenging process, certainly when it comes to designing learning for this goal. The most central place in which I have grown and will likely be the fundamental transformation in my practice is feedback, as described in model three. One particular reading from Hattie, J. & Timperley, H. (2007) entitled “The Power of Feedback” blew my mind.

I think I read the article at least three times and have shared it with a third of my colleagues. Feedback is everything. It is a critical component of my practice that has been painfully absent. And because my feedback has been so scant, student growth through my assessments has been limited.

I was continually giving summative assessments and expecting them to memorize and regurgitate, no matter if I had moved away from multiple-choice or not. It was the same philosophy driving me. Moreover, I’ve found through module five that a classroom management system (CMS) can make the quantity demands for quality feedback rather doable—even easy at times. The right tech tools can transform teaching and learning in fundamental and powerful ways. In particular, I found Canvas LMS to be a beneficial tool concerning the realities of classes full of students and hundreds of items to give feedback on.

One area that I see productive potential in is digital games used for assessments. Module 6 of CEP813 addressed this concept, and, frankly, it was a difficult one. It was not nearly as fun or as easy as I imagined. I believe games can and will be a powerful method through which my students learn and through which I assess, but I need to think deeply about how it functions more effectively for my goals as an educator. On the whole, my understanding of assessment for formative “checks” and adjustments has taken on a rich, complex character.

Assessments as mirrors are the opportunities students have for metacognitive reflection on their understanding, strengths, and growth areas. Months ago, I imagined helping students look themselves in an internal cognitive mirror to assess themselves. I still believe this is a fundamental aspect of the assessment. Where I have grown in this understanding is from Hattie & Timperley (2007) on moving students into self-regulation. I want to develop active learning and promote self-regulation in a problem-based, project-based learning environment. Promoting self-regulation through quality feedback will be crucial to this development. As introduced to my peers and me in module 4, digital portfolios can be an incredible tool for metacognition and summative assessment. Having students reflect on their learning, review their work, and construct a portfolio or showcase demonstrating their learning is a powerful act of self-awareness. Indeed, having students indicate areas of growth and “what’s next” in a portfolio is essential to overall learning and growing beyond the classroom.

Assessments as pageants are demonstrations of learning, like my kindergarten-lion-tamer-circus showcase. I had learned a lot about tigers and lion tamers, and we put on a big exhibition where my classmates and I acted like animals and keepers. It was cute, I am sure. But I doubt that this “assessment” was an excellent example of my learning—not that any of the picture-snapping parents cared at that moment. Summative assessments are activities, tasks, and assignments through which a teacher assesses the already-acquired knowledge or skill of the student. Constructing this assessment is central to all other designed learning before this showcase. As described in module two in CEP813, building toward this goal is central to the Understanding by Design (UBD) approach.

Ultimately, the purpose of any learning is transference into another domain of knowledge. This showcase should confirm and release students into the continued application of the acquired knowledge beyond the classroom. Indeed, UBD and transference are going to be one of a few critical areas of focus this year in my class. I intend to ask myself continually whether this assignment builds toward transference into these students real lives.

This course on Assessments and Technology has been one of the more challenging topics. I believe it has been so because it has challenged many vital aspects of my practice on a fundamental level. It is not just enough to know the theoretical differences between assessment types. I am determined that my student of assessments forces me to rethink and redesign much of what I do daily. Through this course and its various tasks, I have already begun some of this work. One of the assessments that I am most proud of is my design of a learning experience in Canvas LMS. Through it, I created a variety of methods for students to learn the material through some direct instruction or research according to the principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL).

Students also engage in critical thinking discussions with their teacher and each other. Finally, students get to chose how to express their understanding through creativity and making by selecting one of several options. This last creation is an opportunity for quality feedback and iteration for the students. This assessment design was heavily influenced by ideas from all the units covered in the course.

A key area of growth that I will continue to develop further is game-based learning, especially using technology and leveraging authentic learning and assessment. While I believe that my Twine game was creative and focused on the internal grammar of aspects of the content, it fell short on external grammar. Developing a game that can be effectively used for formative assessment and feedback is essential to me and something I want to create and share for those in my discipline.

On the whole, this course on assessment has been deeply meaningful, insightful, and full of joyful “Ahhhhahhhha” ‘s and frustrated reflections on my practice. I walk from this course a better teacher, taking with me a more reflective questioning of the “whys” and “hows” of my classroom assessments.

REFERENCES

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112.

@jonathandkeck Twitter Thread

A Critical Evaluation of History Gamification

Posted on Aug 12, 2019 Leave a Comment

Dungeons and Dragons-style gameplay is a natural form that lends itself to the Twine platform. Immersive storytelling is compelling, especially when one gets to make their own choices on how the story unfolds. This is especially true of young learners tackling abstract concepts from hundreds of years ago as the discipline of history demands. I recently played a Twine game entitled “The Mines of Tos Mett,” that told the story of a dwarf clan that set out to find more abundant veins of precious metal. Alas! They discovered that they needed the financial patronage of the lord of their homeland to sustain them. This game was really about the early American colonies and the same dilemma in which that found themselves in the new New World. Indeed, it required the aid of the King of England as the Dwarves did of Elder Gregor. While I know that this is the case because I know a little history, some direct instruction would be needed for younger students. This information would be vital to contextualize some of this semiotic domain considering the narrative itself is not the internal grammar per se, but the underlying thematic story. This game is an early draft and certainly has potential. Summoning my inner 5th-grader, for whom this game was designed, I would say that the lack of media makes for a less engaging experience. Moreover, many of the choices that I selected resulted in incomplete storylines. But I can imagine how exciting and immersive this game could be with some well-placed pictures of weather-hardened Dwarves and images of their stressful life.

However compelling, I am unclear how I did or if I had learned anything by the game itself—speaking as a 5th-grader. Perhaps more feedback internal to the game can be designed that could target the external grammar of this discipline. As my colleague who created this has said, this game fits into a broader assessment that requires some direct instruction to contextualize and other tools for feedback. He mentioned verbally speaking with students about their decisions and taking a separate assessment at the end of the game. In the game’s current form, this is certainly needed. As is the case in my attempt at creating a history game, my own focused on the internal grammar of the content but gave little for external grammar and built-in feedback. According to my assessment checklist, this game in its current form does not fulfill critical aspects that I articulated as core values. Much like my own, the “The Mines of Tos Mett” by itself provides little space for critical thinking, creativity, choice (beyond the obvious tools native to Twine), or opportunities for self-regulation. There may be some space for feedback on task and process, especially on the broader lesson design.

It may be history or just me, but designing games that fulfill all that we have learned about assessment is incredibly hard in this semiotic domain. I can see students acting as Archaeologist or Historians fulfilling these ideals, but both this game and my own do not achieve the depths of assessment covered. Reflecting on aspects of assessment, a critical element to making these games successful must be the ability to provide feedback and authentic critical thinking leading to transference into new domains according to UBD (Understanding by Design). While there is much potential for “The Mines of Tos Mett,” figuring out how to create an authentic assessment of external grammar for history and internal feedback through the gameplay is the next step. The same is true of my own game, “Death is Coming: A Black Death Survival Story.”

Games are compelling and have the potential of making that which is abstract, real, exciting, and relevant. Cracking the code for Gamification will lead to new frontiers of deep learning for students.

Historians, join me in continuing the struggle.

Creating History Gameplay with Twine: An Iterative Approach

Posted on Aug 6, 2019 Leave a Comment

Learning through play is powerful. If our task is to move history and social science out of the “boring” category, designing and creating meaningful and fun games is paramount. A week ago I set out to start designing my first digital game using Twine and exploring the Black Death in European History.

While I wrote my plans in detail, I am going to recap a few highlights from that post:

To evaluate and design an effective Game-based learning experience and assessment, educators ought to consider the following key concepts that we will define and explore below: semiotic domains, internal grammar, and external grammar.

A semiotic domain refers to the literacies of any given environment, in this case, the literacies within history. This discipline, like all other environments, has its content properties and symbols. Historians see patterns of cause and effect, continuity and change, and cross-temporal and cultural contextualizations in all human actions and events. “Reading” these patterns is vital to the discipline.

To “read” History, its disciples practice a particular sort of internal grammar through which the discipline functions. Historians reading primary sources, in the original language if possible, and read secondary sources through which historiographies are created to situate our understanding of the topic. This practice is foundational, but historians also study patterns of cause and effect, continuity and change, and comparisons between cultures such that the present can be better understood, and predictions might be made.

But these practices are not done in isolation to run the danger of anchoring our conclusions to misconceptions and unseen bias. Historians and Social Scientists practice a sort of external grammar through which these pitfalls are minimized. Reading, discussing, and debating are the norms within these communities. These collaborations occur through professional presentations and research.

There is a type of procedural rhetoric in any task undertaken that through its use, one may practice and process the requisite skills conducted by a historian. This procedure is valid in traditional approaches to instruction, like reading primary sources, synthesizing that evidence, and writing conclusions and predictions. If this same domain is gamified, alignment needs to be made between the internal and external grammar as well as the tasks are undertaken and skills practiced in the designed game. In truth, this is more difficult than the typical “wow, this video game is about assassins in a Medieval town. Kids would love this, and we’ll learn history!” Assassin’s Creed is tempting. And while it certainly is in the domain, assassinating undesirables while leaping from building to building in an epic session of parkour is not part of the internal or external grammar—though seeing a bunch of historians trying would likely look like this classic scene from the Office.

While less flashy, designing a gamed-based assessment through a tool like Twine will likely serve students. Twine is a non-linear story-telling tool inspired by the classic “choose your own adventure” book series. The software allows a designer to create choice-based events through which a web of events might result in leading to different outcomes. This tool might be leveraged to help students both create and engage in various historical problems. For example, historical actors were forced to make hard choices based on limited information. These choices led to real-life consequences not only for themselves but for their communities and civilizations. Twine certainly could be leveraged to help simulate these sort of choices based on information they know and new information that they would need to interpret.

An exciting and fun assessment in this vein would be a simulation of a rural village in the mid-14th century just as the “Black Death” began to sweep through Europe. In this game, students would take on the role of a village elder in charge of protecting the community. Students would be presented with a series of choices, scenarios, artifacts, and events from which they would need to make choices to ensure the survival of the community. The power of this specific game is that these choices were made by real people in the past and will test their decision making based on evidence, their ability to identify patterns, synthesize information, and make informed predictions about how specific actions might lead to various consequences. These choices reinforce aspects of the internal grammar of Historians. If students make these choices in groups or defend their choices against others at the end of the assessment, aspects of the external grammar are reinforced.

Now having created the first iteration of this game, I see some great potentials and a few pitfalls. But before I give a reflection, please check out the version of this game that I’ve created.

http://philome.la/Jonathandkeck/jonathan-daniel-keck/play

Twine is easy to use and a compelling medium through which to create. It’s free and easy, yes, but to spice it up requires knowing some HTML. And to be honest, that is where I struggled the most. The internet is full of helpful voices and I eventually got things to work somewhat in the way I imagined, but having a little more experience with the tools would be extremely helpful.

I also found it rather easy—too easy—to get swept up in the narrative of the story. Students certainly will find some “Oregon Trail vibes” in this game as a colleague told me. He had fun, so that is a win. He also wanted to know how to survive, because apparently he didn’t through several attempts. It is easy to focus on the “game” and forget the “assessment.” Indeed, I found myself falling into the same trap that I criticized Assassin’s Creed over. Just by experiencing or encountering a historical period and some of its information does not warrant it as a learning medium.

In reflection, the students will experience elements of the internal grammar of the history discipline by reading through scenarios of events and making conclusions based on what they know. However, there is little provided in the external grammar in this current iteration of the game. Ideally, students would have to read primary sources and draw conclusion from the texts, applied to new scenarios. Perhaps adding first-person puzzles using source material might elevate the next iteration of the game.

As I said in my last post on this game as an assessment:

Reflecting on the assessment in its current form, the game falls short in a few key areas according to my Assessment Checklist. The things that I articulated as critical values are the following: (1) critical thinking, (2) creativity, (3) feedback on task and process, (4) opportunities for self-regulated learning, and (5) facilitate multiple means of action and expression. Since this activity is already created for them, creativity will not play a significant role in this assessment. There will also be minimal opportunity for self-regulation (4) and choice in action and expression (5). This assessment certainly does provide an opportunity for some critical thinking (1) and an opportunity for feedback on task and process (3). To some extent, the act of making choices in a digital “chose your own adventure” style game will feel creative since students will get to chose their own story.

Creating a game that fulfills these demands will be tricky and some core elements will need to be revised and revised.

However, making history alive with creativity and fun is critical to the future of the discipline. I will not sacrifice meaningfulness for this fun, but I am convinced that both can exist together in the same assessment. While designing meaningful and fun games is complicated, its value to the students learning is tremendous.

ASSESSMENT CREATION AND CANVAS

Posted on Jul 18, 2019 Leave a Comment

Designing creative assessments and facilitating critical thinking through choice in the mode and expression of learning is fundamental to my approach in this assessment. I have been developing an assessment checklist to assist in designing learning experiences and assessments that align with these values.

This assignment was designed for AP World History and World History students. By learning about the first law codes of Mesopotamia and reflecting on this learning through creating according to their choice, students of various learning needs and preferences benefit.

Check out this quick video on the assessment and some of my thoughts.

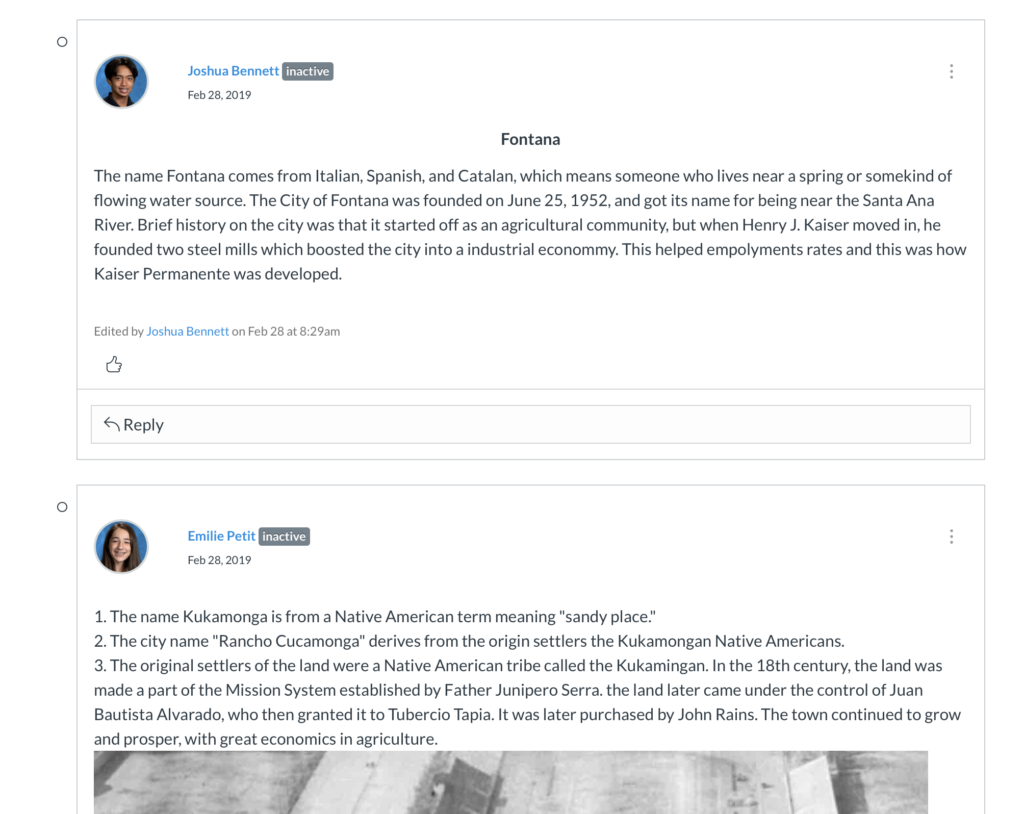

Critical to this assessment is the ability to create and submit through Canvas. The first assessment is a discussion in which students respond to a prompt that calls into question the utility of written law codes. Students are to argue against the claim and discuss why written law codes are not overrated. One nice feature of this discussion is that students will not see other students responses until they respond first. As the teacher, I will engage students in the discussion to prompt deeper thinking and connect various student claims to one another by pointing out various interpretations. In a certain sense, this is a digital socratic discussion in which I will ask leading questions and incite thinking and dialogue. In particular, I am looking for students to make historical claims and cite evidence to back-up their claim. It is these historical claims and their interpretation that will facilitate deeper critical thinking concerning patterns and reasons skills associated with the discipline. This critical thinking is the first item on the Assessment Checklist.

The next part of the assessment focused on a student-choice creation and demonstration of learning. This creation does not take place in Canvas but can be done through various mediums—both low tech and tech. All assignments are submitted through Canvas, however. If a student chose to express themselves through a physical medium, they will document this digitally and submit through Canvas. If digital, Canvas supports almost all file formats for upload. And this choice is central to item five on the Assessment Checklist. Students have a choice both in the act and expression of their learning by choosing the medium and format. Whatever the medium, students are empowered to express themselves in the ways that they choose. Moreover, students are also given choices in how they want to consume the information and learn as well. This choice is central to the learning process and is intended to fulfill the needs and preferences of all students according to Universal Design for Learning principles.

This choice is also important for students’ creativity. Students can be creative and develop and design comics, videos, or skits to fulfill the second item on the checklist concerning creativity. Students also have a choice to express themselves through less creative means by writing a paper or conducting a video analysis. These latter choices aren’t creative and thus do not necessarily fulfill the second item on the checklist, but students have the choice to not be creative in an arts medium. And this is central to the fifth item on the checklist for empowering student voice and choice. Since creativity is important, the role of the teacher would be to slowly encourage integrating creativity and creation into mediums with which the student is comfortable.

The act of design and creation lends itself to self-regulation and reflection on their own work, facilitated by the feedback of the teacher. Item three is intended to encourage quality feedback on the content and process of the student’s work. This can be facilitated through discussion, photos, and questions in the Speedgrader and various communication tools in Canvas. Students and teachers need not wait until the creation is finished and submitted for the student to receive feedback. Check-ins and progress discussions are easy in Canvas. This discussion is vital to helpful formative feedback on the content and process. And this feedback drives students toward self-regulation (item four) by having them evaluate their own progress according to the feedback given by the teacher.

This critical and creative process of design and creation through student choice projects, empowered by meaningful feedback and self regulation is central to student transference into new scenarios and domains of knowledge.

The tools in Canvas serve this purpose well in an online and blended environment.

ASSESSING CANVAS ASSESSMENT TOOLS

Posted on Jul 14, 2019 Leave a Comment

Canvas is perhaps one of the most popular and quickly rising stars among the online learning platforms being used by colleges and K-12 schools. The company prides itself on being composed of former teachers who know education and know first hand what teaching and running a classroom is like. They claim that this is what makes them different as opposed to other tech companies making and selling Classroom Management Systems (CMS). One critical aspect that all CMS needs to provide is a robust and useful system of tools by which teachers can provide assessments and feedback to students and they, in turn, can use the tools to learn and grow.

Finding the right CMS is not easy or often not cheap. If teachers and students are going to invest a ton of time and money into a learning management system, they need a holistic picture and review of the assessment tools.

To that end, I have set out to review and assess Canvas’ assessment tools.

General functionality, access, and privacy

In general, all communication and content are visible only by the student creating the content, any observer they have attached to their account, the teacher, and any administrator with universal permissions.

Each student can securely connect their account to another observer through a secret token. This observer is a digital shadow of the student, seeing all content and communication. This shadow feature is designed for parent and guardian involvement in a K-12 environment. The transparency for internal purposes is reassuring. The observer can see the same analytics, communication, assignments, submissions, feedback, and grades as the student. The observer role can only be established by the student, a teacher, or a universal administrator. The link between observer and student cannot be established without account access to the student. Once an observer role is established, the account is visible to the teacher and the universal administrator. No hidden observers can be created of which the student or school would not be aware.

Universal administrators are those who have system-wide control and can see and edit all content on the platform. The school establishes these administrators.

Canvas support staff also have access to all the data available and use this data in a few ways. According to their privacy policy, Canvas applies the data to market certain Canvas products to account holders and instructors. Student and system-wide data are used for maintenance, customer service, and by the technical team to help fulfill the purpose of the system on campus. Sensitive student data is not given to third-parties. It does, however, collect and make visible all system use data to the teacher. Login frequency, time spent on site, and time of use are part of the data points in the Analytics feature (discussed below) that are intended to be used as part of a holistic picture of assessment.

Inbox

The inbox feature is an internal mailbox through which students and teachers can communicate with one another. This feature is a useful tool for peer communication and for communication and feedback between student and teacher.

Unless used with multiple people in the email, this tool is private to the student and any person in an observer role with that student.

While this isn’t an assessment tool, it is a means by which a teacher can give feedback. Digital files may also be attached, linking to other methods of feedback other than typed writing.

Announcements

Teachers can make universal announcements to the whole class. This communication is not an appropriate way to provide personal feedback on an assessment, but it can be used to give general feedback on overall performance.

Assignments/Pages

Teachers create assignments in Canvas with various instructions and rules regarding tools and submission. Teachers can add content, videos, or anything really for those who know a little code. The affordances and constrains about this content primarily depend on how teachers use the feature. Generally, it would be used to provide instructions for an assessment.

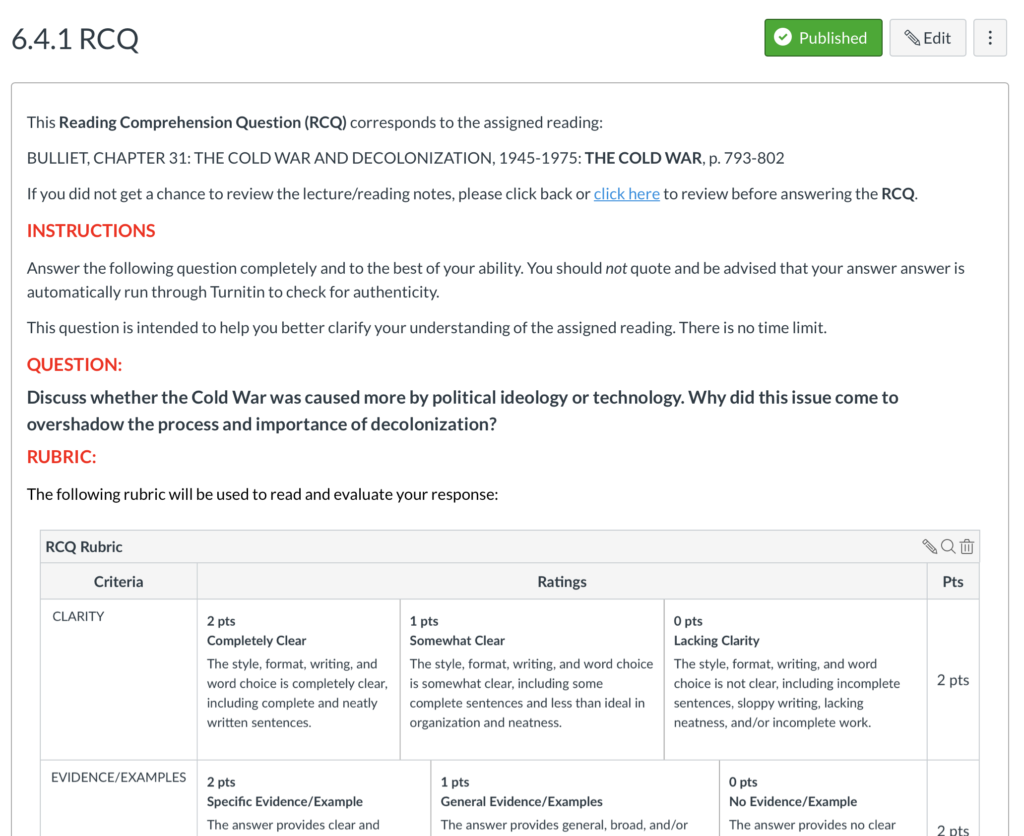

Rubrics

Teachers can create rubrics from scratch or use any that the school has established. These rubrics appear at the bottom of the page of each attached assessment. These rubrics are visible to all users. Perhaps the best feature is that these rubrics also appear in the SpeedGrader and are clickable, automatically applying those points to the grade book and highlighting the selected options for the students. Combined with the other features in the SpeedGrader (reviewed below), students can receive feedback in a variety of ways from their teacher.

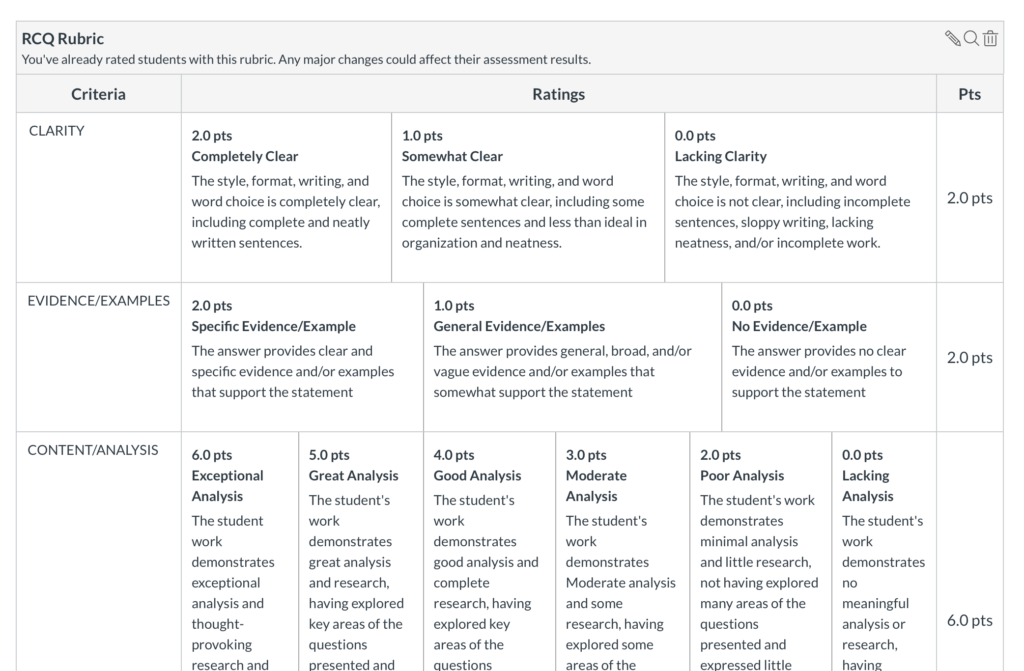

Quizzes.Next

This feature tool is used to create assessments of various kinds. Multiple choices, fill in the blank, essay, matching, ordering, categorization, and true-and-false are some of the traditional formats. Others like “Hot Spot” ask students to touch particular parts of an image to identify and locate something. Teachers can load or create their question banks. Auto feedback responses can also be created that provide explanations of questions and answers—whether marked correct or incorrect.

This tool is well designed for diverse ways of assessing with quick feedback for most types of questions. Since this platform is online, teachers do need to know that asking rote memorization questions with this tool will often result in students leaving the platform and looking up the answer. If that is the designed purpose, then this tool will work well. However, if a teacher wanted to give a controlled test that confined students to the test, a third-party tool would need to be used to restrict student movement.

With this in mind, this Quizzes.next has some powerful features that if used correctly, can result in quick feedback and formative assessment information for the teacher. However, depending on how the questions are designed, this tool may not be appropriate for summative assessments.

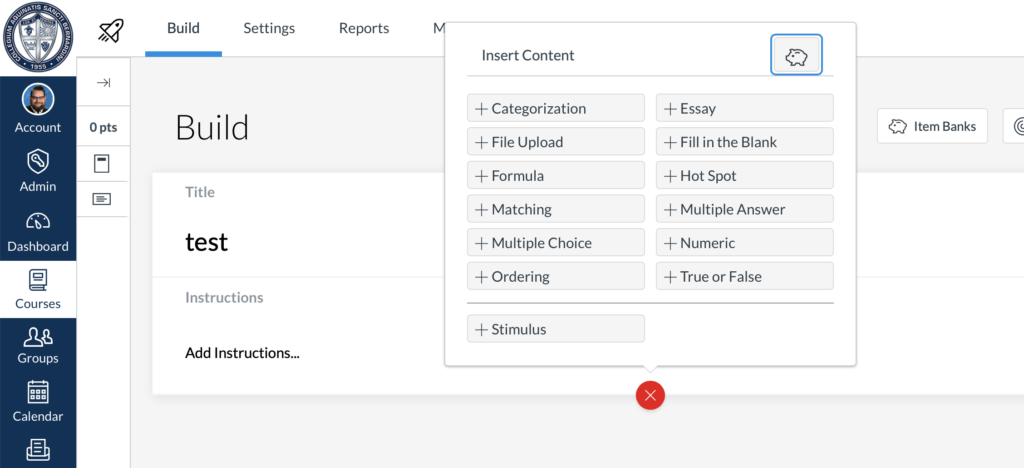

Mastery Paths

Connected to the quizzes.next feature is a tool that instantaneously directs students down different designed pathways according to student results. These pathways can be designed to support reteaching or provide a more challenging path of assignments according to the needs of individual students.

If designed well, this feedback feature can instantly re-target specific knowledge gaps and provide more opportunities to learn. Constraints concerning this feature are also those for the quizzes. If this automated feedback is all that is provided, students may not receive the kind of personal feedback that would serve best. In terms of functionality, this tool would function best for assessments with predetermined answers, like multiple-choice questions. These tools can be used for larger projects, but the feedback in that situation would best be given from the teacher in writing or from a video.

Discussion

A teacher can facilitate a discussion with students in which all see and respond to one another in a digital dialogue. One exciting feature is the ability to constrict the view of students so that they cannot see their peer’s responses until they personally have commented. Then all other’s answers are displayed. This feature can help ensure that students responses are authentic and personal. This feature can either have an entry in the grade book or not.

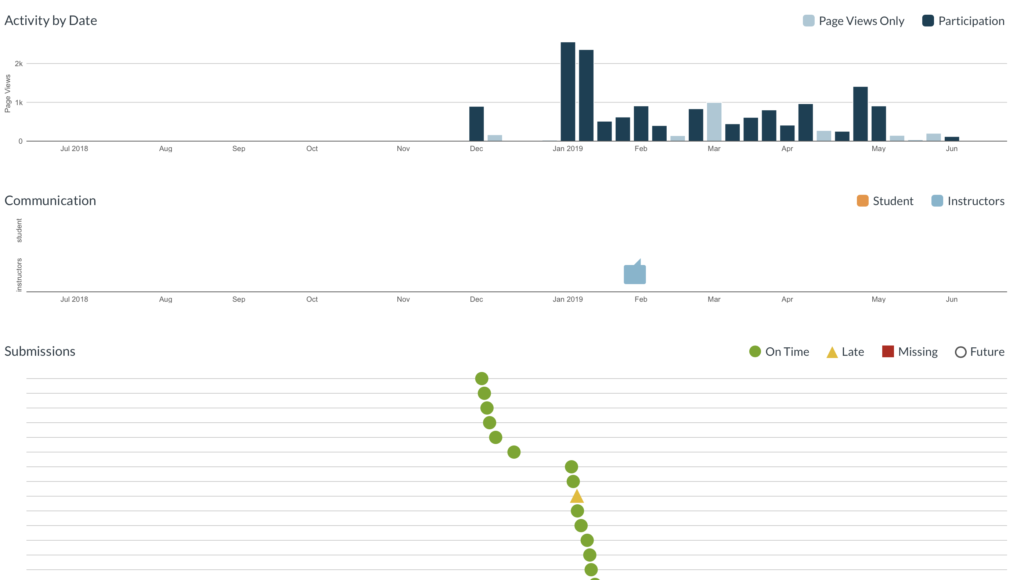

Student Analytics

A detailed breakdown of data is provided for each student. Each student has access to their data, as well as the teacher of the course. This data includes hours on the platform and the frequency of use. It also provides information on the rate of on-time and late submissions for assignments. This data is readily available to both students and teachers. The information can help teachers see a holistic picture of the student’s activity.

This data is used by Canvas for support services but is not shared with any third-parties.

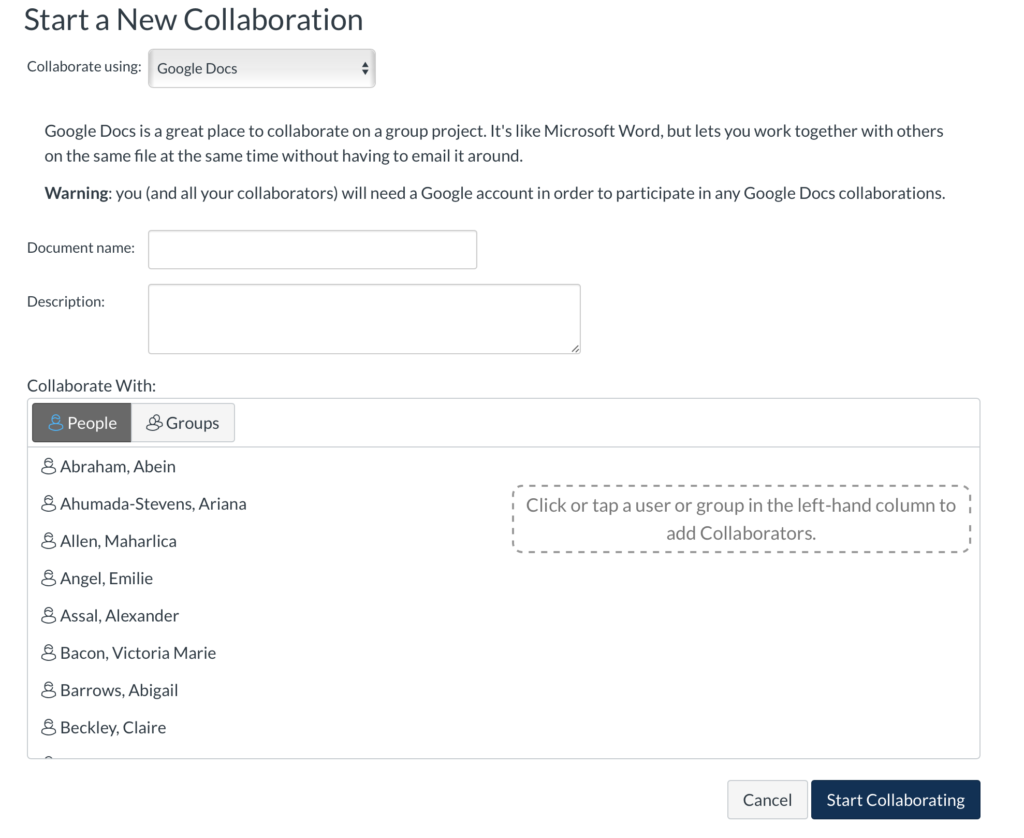

Student Collaborations

Students and teachers can set groups with whom they can collaborate through Google tools through the Google LTI (Learning Tools Interoperability). This integration allows third-party groups to create tools that can be used internally within another system, in this case, Canvas. These students will collaborate on various Google tools like Slides or Docs without leaving the Canvas environment. Moreover, when students in a collaboration submit work, it sends the work in each student’s Canvas assignment. Feedback and grades can either be given as a whole or by individual according to the teachers and students preferences and needs. One of the constraints is that Google often requests re-authentication every few weeks. This permission can be a nice security feature, or it can be frustrating depending on the user.

Groups

Teachers can predesign or randomly create an unlimited number of groups and breakdowns, whether groups of 3 or 5. These groups are native to the Canvas LMS rather than running through the Google LTI. Group assignments can be created in the assignments tool and will grade these students together unless otherwise designated to grade individually. One nice feature is that once one student submits the assignment, it sends it for the whole group.

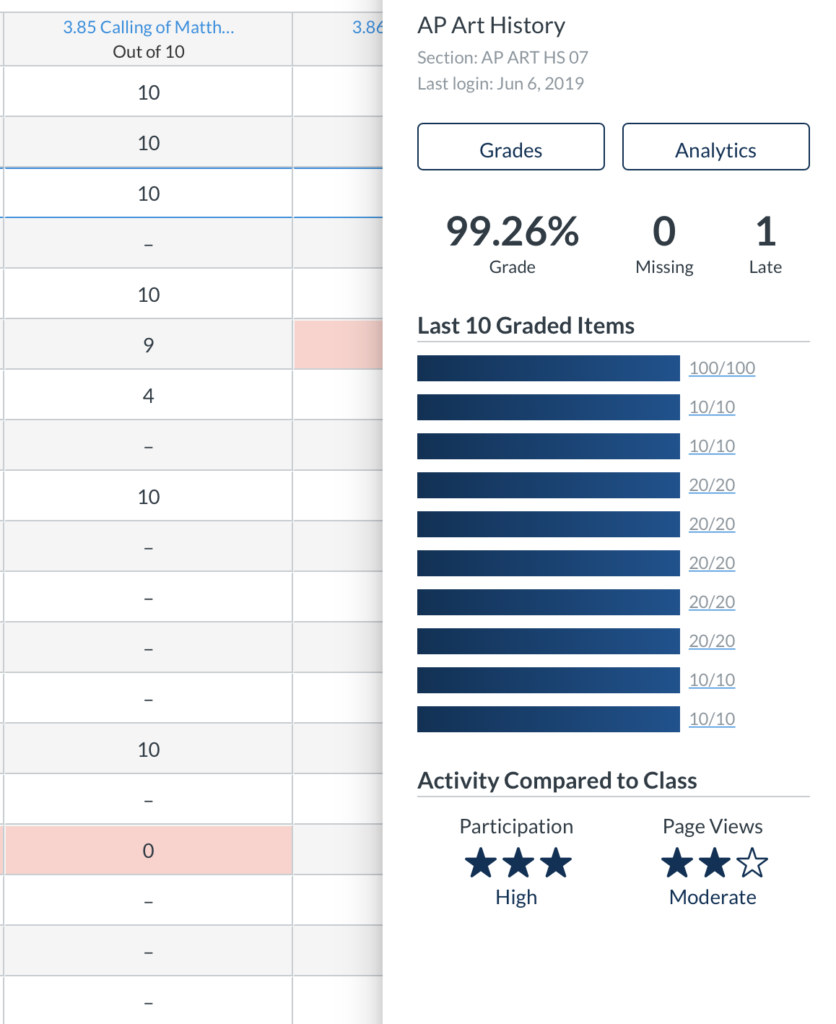

Grade book: Student Data Slider

This feature is for instructors as a tool for quick information on student performance in the course. The slider provides a distilled collection of analytic data about activity, submissions, grades, etc. This information can be helpful for a teacher to identify trends in student performance and activity. This information can then be used to help provide meaningful feedback.

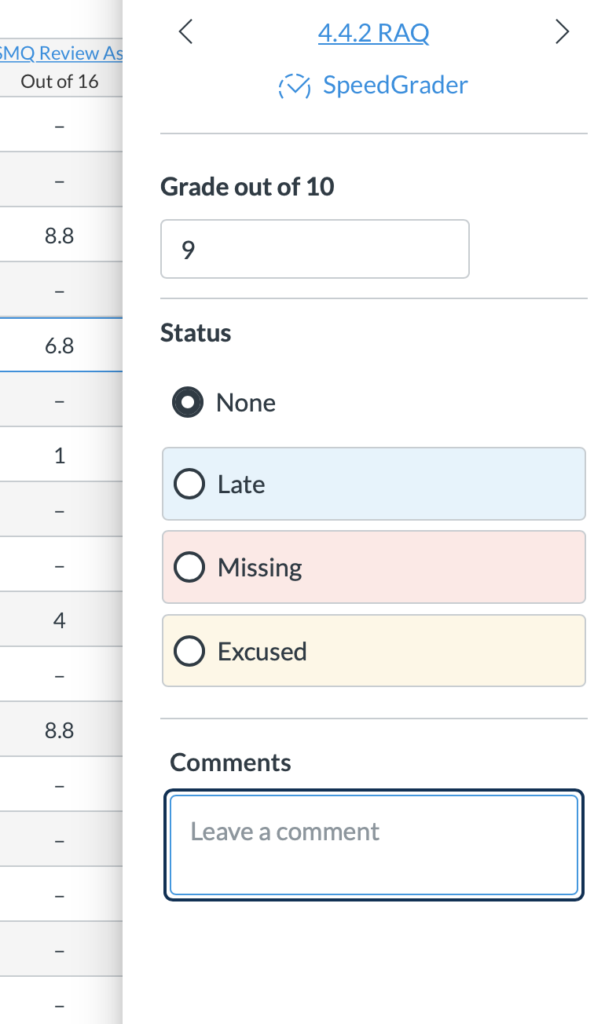

Gradebook: Feedback Slider

While in the grade book, each assignment can be clicked on, and a slider provides grading and feedback options. Here an assignment can be marked late, missing, or excused. A teacher can set late or missing assignments to automatically give a reduction of points or assign zeros according to their wishes. A constraint of this feature is that auto-filling grades can be frustrating to students when they have a circumstance that prevented them from submitting on time. Teachers ought to be careful about how they use this tool. The commenting feature in the feedback slider is convenient and focused. Rather than an email referring to an assignment, teachers and students can discuss the task, ask questions, and dialogue in the same space as the grade. This same conversation is also copied over to the SpeedGrader feature.

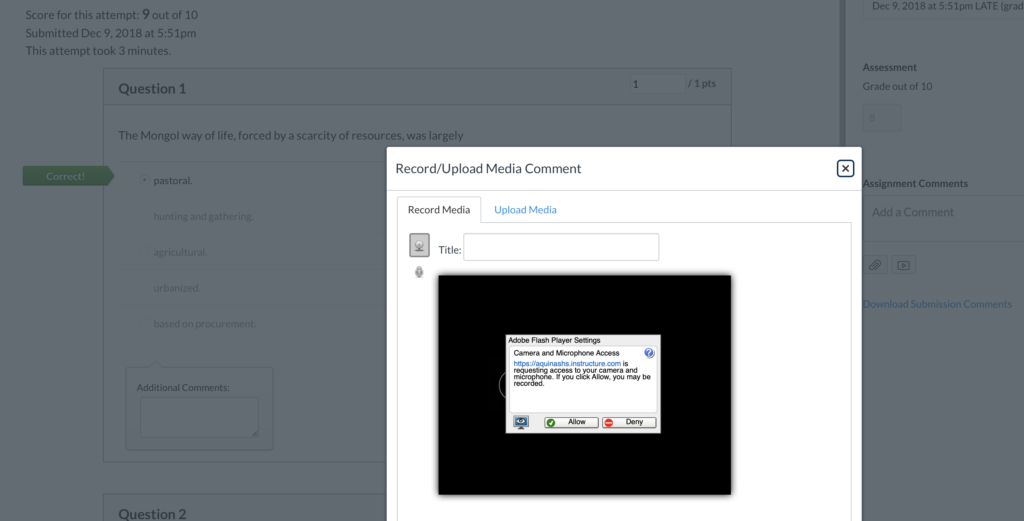

SpeedGrader Feedback

If a teacher uses the SpeedGrader tool, the students’ assignment appears on the left panel screen, and feedback tools appear on the right. If the assignment is a document, teachers can write on the document using a writing tool (most likely if they are using a tablet) or can highlight and type. A Google Doc will also appear if the teacher established and used an LTI. All the Google tool features appear and are operable. Students may also post videos or some other evidence that appears in the box fully functioning and reviewable without leaving the SpeedGrader tool. Teachers can provide more feedback and dialogue with students in this tool. Teachers can natively record video responses to the students work and can also upload other links as well. It is called the SpeedGrader because teachers can swipe or click in either direction, which brings the next student’s content and tools to the current page.

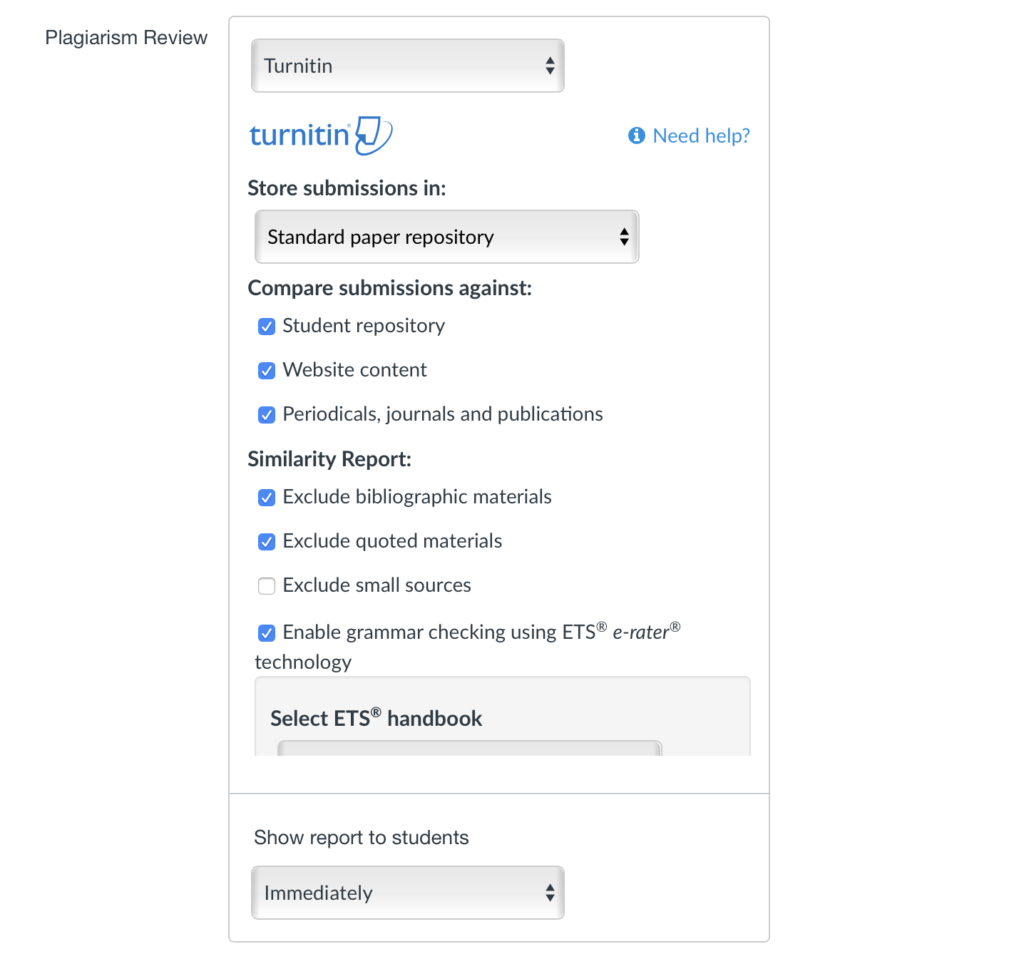

Turnitin LTI

One of the most common LTIs used in Canvas is Turnitin, an originally checker and tool to provide feedback to students. Once this LTI is turned on, teachers can use all the features of Turnitin in every assignment submission with writing. This tool does not extend to Discussions. Originality reports are automatically generated when an assigned is submitted and is visible to the teacher and student. The Gradebook also highlights the assignment with a color code associated with the originality (or in this case unoriginality) of the work, red for over 50%, yellow for 25% to 49%, green for 0% to 24%, and blue for matches of only 20 words in their database. This information can be used to provide feedback to students, but on its own does not serve as quality feedback. Students can be flagged for excessive quoting, as well as plagiarism. Students need teachers to use this information in their discussion concerning their work.

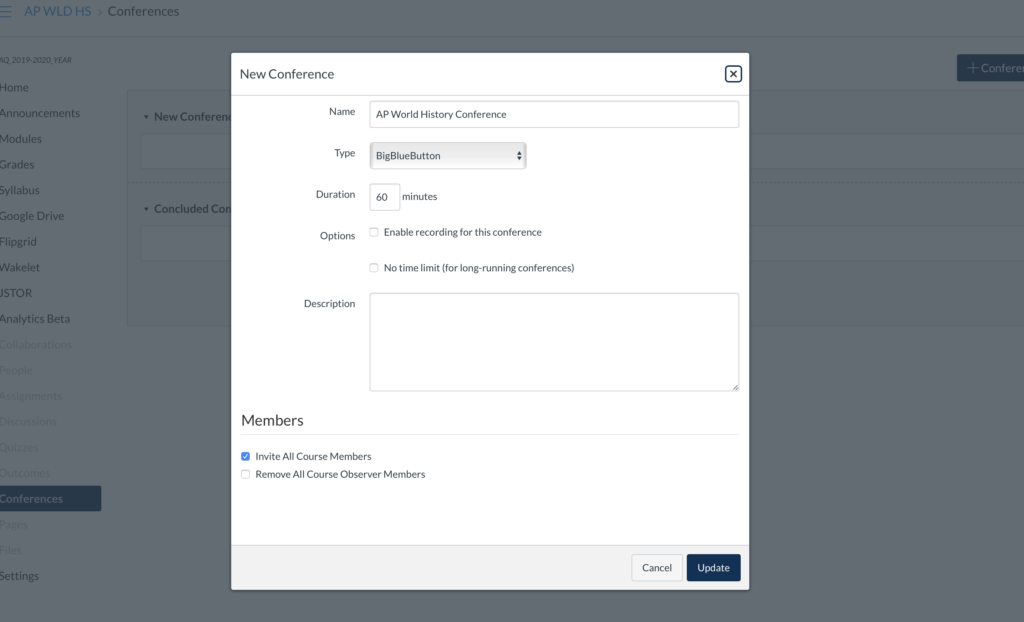

Online Conferences

Teachers can establish online video conferences natively through Canvas without needing to use third-party tools like Zoom or Skype. Since this tool is browser-based, the student only needs to log in to their account to gain access to a scheduled conference. The affordance is that this tool is used in the same ecosystem as all other aspects of the learning. This interconnectedness helps alleviate student frustration in remembering different tools and ways in which teachers want student work submitted. However, Zoom does have a better tool than that provided by Canvas natively.

Conclusion

Other than when mentioned, all of these features in Canvas together allow for a robust formative assessment ecosystem. There are numerous ways to quickly provide meaningful, timely, and personal feedback to each student. Canvas is weaker in secure tools for summative assessment. The LMS is a browser-based tool and thus cannot be secured for traditional summative assessments because a student cannot be restricted from looking up information. However, if a teacher does not use this type of assessment, but instead focuses on creating and design, the Canvas tools work well. The purpose determines the utility.

Assessment Design Checklist 3.0

Posted on Jul 6, 2019 Leave a Comment

When designing a learning experience, there are hundreds of concerns that run through the teacher’s mind. Confusion might be one word to describe it, but it often feels like multivariable calculus. Indeed, the lesson planning and assessment design process are best captured in the following gifs.

Fortunately, a class I am currently taking in the MAET program at Michigan State University on Assessments has a solution. The course has us create a checklist by which we can evaluate our assessment design for necessary affective components. The checklist only has five essential features to check for, but obviously, there are dozens of things that I would like to add. For now, five is more than enough! And that is because this is no mere check-box checklist, but one backed by research and evidence to the degree that it takes hours of work to get one item written out.

Throughout the iterative process, I designed three versions of this checklist. I can tell you that the hardest part has been getting the research and evidence right. Even then, I’ve found that so much of my thinking is intertwined concerning assessments. Indeed, I know that the components of effective assessment design are a web that interconnects and supports individual strains that together can capture and hold-up students and their learning. That’s where the metaphor ends because there is no bloodsucking and desiccation—sorry vampires out there. However, what I have written at times feels less like the intricate and beautiful web that I know it really can be and more like the Gordian knot.

Even though this assignment is coming to a close, I am determined to add other aspects to this checklist covering Universal Design by Learning (UDL), Depth of Knowledge (DOK), Understanding by Design (UbD), among many other concerns.

However, for now, here is the current version of my Assessment Design Checklist 3.0